A tale of how a 1912 IHC Highwheeler begat a 1906 Cadillac…

It all started out with a search for some parts for a 1912 International Highwheeler. Somewhere through the grapevine, I heard about some Highwheeler parts in Washington State. I tracked them down and called their owner.

He stated that they were not for sale but possibly could be had through a trade. I asked what he was looking for and he listed a series of cars that I did not have any parts for. One car the he mentioned was a One Cylinder Cadillac. Between 1903 and 1908, Cadillac cars only had one cylinder and therefore are called One Cylinder Cadillacs.

I did not have any parts but started searching my memory banks for possible sources. I remembered that a gentleman in my hometown had a 1906 Cadillac. On my next trip to visit my parents I stopped in to see this gentleman.

I explained that I was looking for Cadillac parts that I could buy to trade for Highwheeler parts. He indicated that he had an extra engine but was not sure if he wanted to sell it. I told him that if he ever decided to sell it, I would be interested.

A couple of months passed. I was talking to my father on the phone and he said that the gentleman had called and said the engine was for sale. My father had no further details. I called the gentleman and asked for the details.

He spent the first ten minutes telling me how rare the engine is and how valuable it was. I then asked the price. The response was $450. I said “sold” since I knew that the engine was worth much more that that. A couple of weeks later I went and picked it up.

Not knowing anything about One Cylinder Cadillacs, I attempted to figure out what year it was. I found the serial number and it was 345. I did some research and found that Cadillac built about 2000 cars in 1903, their first year of production.

Now this is where I got to use this expensive education of mine. I figured that if 2000 Cadillacs were built in 1903 and the serial number on the engine I had was 345, I could deduce that the engine came in a 1903 car. Isn’t higher education wonderful?

I then made a call back to Washington State to attempt to make a trade. I described what I had and that I would be willing to make a trade. The response from the other end was “is that all you have of the car?”. The guy did not have a One Cylinder Cadillac and was not willing to trade unless I could provide more of a car. Now I am left holding the bag, or in this case the engine.

I then started to talk to people who know of or had One Cylinder Cadillacs. I would tell them that I had a 1903 engine and inevitably the response would be “no you don’t “. I would ask why they did not believe it was a 1903 engine and I would be told that there is a very tight One Cylinder Cadillac following and that all the 1903 parts are known of.

There is no way that I could have discovered an unknown 1903 engine. They would then ask about some of the dimensions and casting marks. Their next comment would be that it sure sounds like a 1903 engine.

The grapevine then came into play again. The word got out that I had a 1903 Cadillac engine. Calls starting coming in. It seems that there are quite a few 1903 Cadillacs out here with newer engines in them.

I think I got calls from about 10 people interested in buying the engine. Then offers started coming in. The highest offer for the engine, sight unseen, was $4000. In all cases I stated that it was not for sale. The more I talked to people, the more I thought I wanted a One Cylinder Cadillac.

One of the people who called was a gentleman from Nebraska by the name of Homer. I had never heard of Homer and did not know anything about Homer. But, Homer would call me once a month to see what was happening with the 1903 Cadillac engine. I kept telling him that it was safe and sound, I did not need to do anything with it, it did not make any noise, I did not need to feed it, it was not bothering anyone and I was thinking about keeping it and building a car around it.

Homer said I would never find enough parts to build a 1903 Cadillac. To which I replied that it did not need to be a 1903. I would be happy with any year One Cylinder Cadillac. That was my demise in keeping the engine. Homer then said he would see what he could do in trading material and call me back.

A couple of weeks went by and Homer called. He said he had parts to a 1906 Cadillac that he would sell me if he could get the 1903 engine. He indicated that he could not trade outright since he would be supplying about ¾ of the 1906. The price was my engine plus $3500. I indicated that I did not have that kind of money and that I could not commit to the deal.

I did know however that the parts that he was offering were worth much more than his asking price. But, since he was so hot on the engine, I figured I would see if I could get a better deal. Then the monthly calls from Homer resumed. I kept telling him that I was interested but needed a better deal.

He would not budge on the price. Then one time he called, he asked what else I was working on and needed parts for. I told him what I had and needed. He indicated that he might be able to help me out on my 1907 Buick.

He indicated that he would see what he could do and call me back. On the next call from Homer he asked if an engine for my 1907 Buick would make the deal. He said that he could not just include it and that the price would go up by $1500. I again said that I did not have that kind of money, hoping for a better deal.

Since each year I make a trip to Wisconsin to visit my wife’s parents and attend the car show in Iola, Wisconsin, Homer and I agreed that I would put the engine in the truck and that I would stop by and see him.

Now who is Homer? In my discussion with old car people, I started asking questions and getting information about Homer. Most people said that Homer is hard to deal with and that if you could deal with him, he always gets the better end of the deal. It turns out that Homer is an 80 something year old widower who has been collecting early cars and parts since he was a pup. He has a collection that is totally unbelievable.

He has two restored One Cylinder Cadillacs, probably 10 other One Cylinder Cadillac engines and probably enough parts to put together about another 5 cars. He also has early Buick cars and parts, early Brush cars and parts, early Ford cars and parts (both Model T and before), 1909-10 Cadillac cars and parts and who knows what else.

If it does not have gaslights, he is not interested. Electric lights came out around 1912. He has buildings and tractor-trailers loaded with cars and parts.

For that summer’s trip, I had arranged to pick up parts for an IHC Highwheeler in Arkansas, Buick Parts in Wyoming and Buick parts in Iowa. By the time I got to Homer’s, I had a truck and trailer full of parts. We met for the first time when I pulled into the driveway but we were not strangers since we had many phone conversations.

Homer looked the engine all over and stated that it was just as I had described it and that it was what he was looking for. We then went into his barn where he had laid out the 1906 Cadillac parts (3/4 of the car) and the 1907 Buick engine. The parts were in very good condition. I tried one last time to get a better deal. He was firm on his side of the deal. The money exchanged hands and the parts were transferred.

We then took a tour of his collection, which took several hours. I was then on my way, the proud owner of a 1906 Cadillac and an engine for my 1907 Buick. By the time I got home I had traveled about 6000 miles in two weeks.

And that is how a 1912 IHC Highwheeler begat a 1906 Cadillac. Homer turned out to be a very pleasant man. Since my first trip to make the trade, I have been back to see Homer every summer. I stay with him for a couple of days and we always find something to trade, but that is fodder for other stories.

Homer has been very good to me and has always allowed me to borrow anything that I need to copy for anything that I may be working on. Our dealings have been fair and I look forward to each visit.

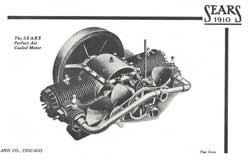

Many VAE members have seen Bill Erskine’s Sears Motor Buggy. Some have even seen him arrive at a VAE meet with the crated motor buggy just like it arrive by train from Sears, Roebuck in 1910 and watched him assemble the vehicle.

Many VAE members have seen Bill Erskine’s Sears Motor Buggy. Some have even seen him arrive at a VAE meet with the crated motor buggy just like it arrive by train from Sears, Roebuck in 1910 and watched him assemble the vehicle. The engine was lubricated by an “oiler”, essentially a tank mounted under the seat which had several adjustable drip feeds with separate lines to the engine bearings and other areas. All components of the transmission were exposed, so several bearings and pivots had to be oiled or greased manually from time to time.

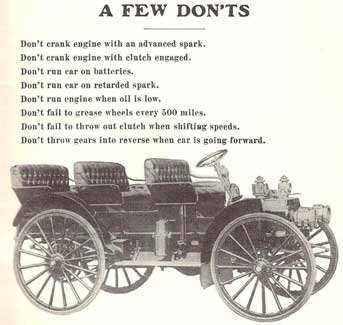

The engine was lubricated by an “oiler”, essentially a tank mounted under the seat which had several adjustable drip feeds with separate lines to the engine bearings and other areas. All components of the transmission were exposed, so several bearings and pivots had to be oiled or greased manually from time to time. Today we call the vehicles “High Wheelers” but the term very likely will confuse any ‘old timers’. Sears had it’s Motor Buggy and International Harvester had its “Auto Buggys” and “Auto Wagons” like the picture to the left. Auto Buggys had a back seat and Auto Wagons did not. IHC made this type auto wagon from about 1909 through about 1915 when the term motor truck slowly took over. IHC made many models of vehicles during this period: from the auto wagon and auto buggy to the roadster and the touring car, in all over 11,000 vehicles were built.

Today we call the vehicles “High Wheelers” but the term very likely will confuse any ‘old timers’. Sears had it’s Motor Buggy and International Harvester had its “Auto Buggys” and “Auto Wagons” like the picture to the left. Auto Buggys had a back seat and Auto Wagons did not. IHC made this type auto wagon from about 1909 through about 1915 when the term motor truck slowly took over. IHC made many models of vehicles during this period: from the auto wagon and auto buggy to the roadster and the touring car, in all over 11,000 vehicles were built.