Recently I went through the annual exercise of getting my old work truck ready for the state inspection. The parking brake did not work. The piece that connects the front and intermediate cables had broken. This is the part that allows for adjustment to take up slack in the cable. It is a simple piece of metal that has a 5/16″ hole on one end to accept the threaded end of the front cable, and a slot at the other end to trap the ball at the front end of the intermediate cable.

Unfortunately, after checking at the dealer and auto parts stores I learned this part is not available anymore.

A check of the local wrecking yards revealed parts no better than the broken part I already had. Frustration led to despair. I realized that this part was manufactured once, so, it could be again. After a little thought I realized I could easily make one.

I took a piece of scrap steel, 3/16″ by 1-1/4″ and cut it to a length of 8″. Next I drilled a 5/16″ hole about an inch and a half from one end, placed it in the vise and bent the end over 90°. This gave me the end for the threaded rod on the front cable.

I took a piece of scrap steel, 3/16″ by 1-1/4″ and cut it to a length of 8″. Next I drilled a 5/16″ hole about an inch and a half from one end, placed it in the vise and bent the end over 90°. This gave me the end for the threaded rod on the front cable.

For the other end that accepts the ball on the end of the intermediate cable, I drilled a 1/4″ hole about 2-1/2″ inches from the end, then drilled a 3/16″ hole about an inch from the end.

I placed the part back in the vise and bent a 3/4″ tab over the other end. I removed the piece from the vise and placed it in my metal chop saw, then made a cut connecting the two holes I had just drilled. This gave me the slot to place the intermediate cable in.

Final cost? One piece of scrap metal and about 10 minutes of time. Often when working on older vehicles we have to manufacture our own parts. Fortunately, with a little time and effort, this is possible.

Please email all inquiries to: Dave

Please email all inquiries to: Dave

or snail mail

32 Turkey Hill Road

Richmond VT 05477

In high school, my car was a 1950 2-door Ford painted black, and had dual exhaust. Two of my classmates had ‘49 Chevies with split exhausts (one of which was done in shop class.) This is when the envy started. How could I make my Ford sound like the Chevies? The answer is: you cannot!

In high school, my car was a 1950 2-door Ford painted black, and had dual exhaust. Two of my classmates had ‘49 Chevies with split exhausts (one of which was done in shop class.) This is when the envy started. How could I make my Ford sound like the Chevies? The answer is: you cannot! Many VAE members have seen Bill Erskine’s Sears Motor Buggy. Some have even seen him arrive at a VAE meet with the crated motor buggy just like it arrive by train from Sears, Roebuck in 1910 and watched him assemble the vehicle.

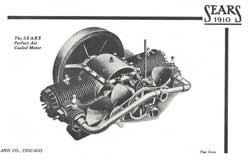

Many VAE members have seen Bill Erskine’s Sears Motor Buggy. Some have even seen him arrive at a VAE meet with the crated motor buggy just like it arrive by train from Sears, Roebuck in 1910 and watched him assemble the vehicle. The engine was lubricated by an “oiler”, essentially a tank mounted under the seat which had several adjustable drip feeds with separate lines to the engine bearings and other areas. All components of the transmission were exposed, so several bearings and pivots had to be oiled or greased manually from time to time.

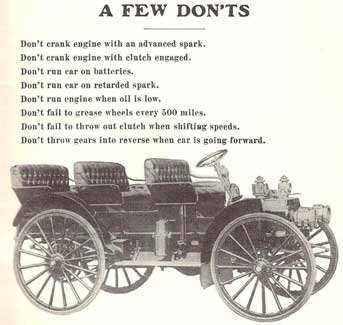

The engine was lubricated by an “oiler”, essentially a tank mounted under the seat which had several adjustable drip feeds with separate lines to the engine bearings and other areas. All components of the transmission were exposed, so several bearings and pivots had to be oiled or greased manually from time to time. Today we call the vehicles “High Wheelers” but the term very likely will confuse any ‘old timers’. Sears had it’s Motor Buggy and International Harvester had its “Auto Buggys” and “Auto Wagons” like the picture to the left. Auto Buggys had a back seat and Auto Wagons did not. IHC made this type auto wagon from about 1909 through about 1915 when the term motor truck slowly took over. IHC made many models of vehicles during this period: from the auto wagon and auto buggy to the roadster and the touring car, in all over 11,000 vehicles were built.

Today we call the vehicles “High Wheelers” but the term very likely will confuse any ‘old timers’. Sears had it’s Motor Buggy and International Harvester had its “Auto Buggys” and “Auto Wagons” like the picture to the left. Auto Buggys had a back seat and Auto Wagons did not. IHC made this type auto wagon from about 1909 through about 1915 when the term motor truck slowly took over. IHC made many models of vehicles during this period: from the auto wagon and auto buggy to the roadster and the touring car, in all over 11,000 vehicles were built.